The Presidents of the USA

| Born | Mar. 15, 1767, Waxhaw settlement, SC./td> |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Education | read law in Salisbury, NC, 1784-87 |

| Military service | ♦ Waxhaw settlement militia, 1780 ♦ Tennessee Militia, 1802-14 ♦ U.S. Army, 1814-18 (Major General). Victorious leader in the battles of Horseshoe Bend and New Orleans. |

| Previous public office | ♦ public prosecutor, Mero District, TN, 1787 ♦ Tennessee Constitutional Convention, 1796 ♦ House of Representatives, 1796-97 ♦ U.S. Senate, 1797-98 ♦ Governor of Florida, 1821 ♦ U.S. Senate, 1823-25 |

| Died | June 8, 1845, near Nashville, Tenn. |

Andrew Jackson was born on the Carolina frontier, the only American President born of immigrant (Irish) parents. His father died just before he was born, soon after arriving from Ireland, and his mother and two brothers died during the revolutionary war.

After the outbreak of the American Revolution, Jackson, barely 13 years old, served as an orderly to Col. William Richardson. Following one engagement, Jackson and his brother were captured by the British and taken to a prison camp. When Jackson refused to clean an officer's boots, the officer slashed him with a sword, leaving a permanent scar on his forehead and left hand. Jackson was the only member of his family to survive the war, and it is generally believed that his harsh, adventuresome, early life developed his strong, aggressive qualities of leadership, his violent temper, and his need for intense loyalty from friends.

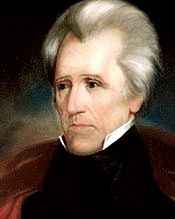

After the war Jackson drifted from one occupation to another and from one relative to another. He squandered a small inheritance and for a time lived a wild, undisciplined life that gave free rein to his passionate nature. He developed lifelong interests in horse racing and cock-fighting and frequently indulged in outrageous practical jokes. Standing just over 6 feet tall, with long, sharp, bony features lighted by intense blue eyes, Jackson presented an imposing figure that gave every impression of a will and need to command.

After learning the saddler's trade, Jackson tried school-teaching for a season or two, then left in 1784 for Salisbury, N. C., where he studied law in a local office. Three years later, licensed to practice law in North Carolina, he migrated to the western district that eventually became Tennessee. Appointed public prosecutor for the district, he took up residence in Nashville.

A successful prosecutor and lawyer, he was particularly useful to creditors who had trouble collecting debts. Since money was scarce in the West, he accepted land in payment for his services and within 10 years became one of the most important landowners in Tennessee. Unfortunately his speculations in land failed, and he spiraled deeply into debt, a misadventure that left him with lasting monetary prejudices. He came to condemn credit because it encouraged speculation and indebtedness. He distrusted the note-issuing, credit-producing aspects of banking and abhorred paper money. He regarded hard money as the only legitimate means by which honest men could engage in business transactions.

While Jackson was emerging as an important citizen by virtue of his land holdings, he also achieved social status by marrying Rachel Donelson, the daughter of one of the region's original settlers. The Jacksons had no children of their own, but they adopted one of Rachel's nephews and named him Andrew Jackson, Jr.

When Congress created the Southwest Territory in 1790, Jackson was appointed an attorney general for the Mero District and judge advocate of the Davidson County militia. In 1796 the northern portion of the territory held a constitutional convention to petition Congress for admission as a state to the Union. Jackson attended the convention as a delegate from his county. Although he played a modest part in the proceedings, one tradition does credit him with suggesting the name of the state: Tennessee, derived from the name of a Cherokee Indian chief.

Jackson helped to draft the state constitution in 1795, served at the state constitutional convention in 1796, and was sent to the U.S. House the following year and then the Senate in 1797, serving one year. He served on the Tennessee Superior Court from 1799 to 1804 but resigned to devote himself to business. Several reverses forced him to sell Hunter's Hill and move to a smaller plantation, the Hermitage. He bred, raised, and raced horses successfully.

In a duel on May 30, 1806, Jackson shot and killed Charles Dickinson for making unflattering remarks about Jackson's wife; one of Dickinson's bullets remained in his chest. In 1813 Jackson was shot in a hotel brawl with Thomas Hart Benton and Jesse Benton, two brothers who dominated politics in Missouri, and the bullet was not removed until 1832.

Jackson took command of the Tennessee state militia during the War of 1812. Fighting the Creek Indians, who were allied with the British, he won the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama in March 1814. This victory ended the Creek War, forcing the tribe to cede more than 23 million acres to the United States.

In May he was commissioned a major general of the regular army. He then captured Pensacola, Florida, and defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. The British suffered more than 2,000 dead, including their commanding general; American losses totaled 8 killed and 13 wounded. These military victories made Jackson, known as Sharp Knife to the Indians and Old Hickory to the Americans, a national figure.

After the war, Jackson fought other Indian tribes, defeating the Chickasaw, the Choctaw, and the Cherokee. In 1818 he commanded troops in the Seminole Wars in Georgia. He invaded Spanish Florida and executed two British subjects who had stirred up an Indian revolt, causing a diplomatic furor. Jackson defeated an attempt by the House of Representatives to censure him. After the United States acquired Florida from Spain, President James Monroe appointed him the first territorial governor.

Jackson was elected to the Senate in 1823, occupying a seat next to Thomas Hart Benton, the man who had nearly killed him in 1813. The two soon became political allies, and Jackson began campaigning for the Presidency. In the election of 1824 he received the most popular and electoral votes of any candidate in the four-person race but not enough to win election. In the contingency election -held because no candidate received a majority of electoral college votes -the House of Representatives chose John Quincy Adams over Jackson and William Crawford. As Speaker of the House, Henry Clay had controlled the key House votes that elected Adams. Adams then named Clay secretary of state, an appointment that led Jackson's followers to charge that a “corrupt bargain” had been made. Jackson resigned from the Senate in 1825 to organize his next run for the Presidency.

By 1828 the number of voters had almost quadrupled, and in every state except South Carolina electors were chosen directly by the voters, not by the state legislatures. Jackson and Martin Van Buren organized state parties to mobilize and turn out this large electorate. The huge turnout in what was the first fully democratic election in the United States gave Jackson an overwhelming popular and electoral college vote over his opponent, John Quincy Adams, who ran on the National Republican ticket. But tragedy marred his victory: between his election and inauguration his wife, Rachel, died.

Jackson's accession to power in Washington was akin to a political, social, and economic revolution. By his clothing, his speech, and his manners, Jackson was a “man of the people” with little in common with the Virginia or Massachusetts aristocrats who had previously sat in the White House. He was a military man with little Washington experience, a man with almost no formal education, and the first “outsider” to win the White House. Jackson had swept away the party-less Era of Good Feelings and soon created a new political party, the Democrats, with a strong Southern and Western base among frontiersmen, small farmers, and workers.

Early in his term Jackson dismissed about one-tenth of the officeholders in Washington and replaced them with his followers. Jackson embraced the principle of rotation in office, in which government officials are appointed on the basis of political ties, rather than a permanent civil service with lifetime appointments.

There was a strong element of personalism in the rule of the hotheaded Jackson, and the Kitchen Cabinet, a small group of favorite advisers-was powerful. Vigorous publicity and violent journalistic attacks on anti-Jacksonians were ably handled by his staff. Party loyalty was intense, and party members were rewarded with government posts in what came to be known as the spoils system. Personal relationships became of utmost importance.

Jackson soon became embroiled in traditional Washington society. Peggy O'Neale, the daughter of a saloon keeper, married Jackson's secretary of war, John Eaton, and was ostracized by other cabinet wives, who claimed she had been having an adulterous affair with Eaton prior to their marriage. Rumors about Mrs. Eaton were spread by the wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun. Jackson took Peggy Eaton's side against the leaders of Washington society.

Later, his disagreement with Calhoun over the Tariff of Abominations of 1828 led to an open split between them. In the spring of 1831 Jackson forced out the three members of the cabinet who would not accept Peggy Eaton. He established the principle, new in American government, that the cabinet secretaries serve at the pleasure of the President and are subordinate to his will.

The dominant issue during Jackson’ s presidency was the Bank War. Jackson took on the Second Bank of the United States, a private corporation created as the linchpin of national economic policy-making. The national government held one-fifth of the bank's stock and kept its deposits there, and the bank's notes were legal tender (currency). On July 10, 1832, Jackson vetoed a bill passed by Congress that would have rechartered the bank, which was due to expire in 1836, attacking it as a law “to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful.” Congress was unable to override his veto.

The issue developed because of Jackson's prejudice against paper money and banks and because of his contention that the Second Bank of the United States (established in 1816) was not only unconstitutional but had failed to establish a sound and uniform currency. Moreover, he suspected the Bank of improper interference in the political process.

Jackson made the veto a major issue in his 1832 reelection campaign. He identified the bank with “special privileges” that the government had given to local bankers affiliated with the national bank. He argued that government should remain neutral among financial institutions. The appeal made Jackson seem like a representative of the common man against the wealthy and privileged, though Jackson had not explicitly called for class conflict.

With Martin Van Buren on his ticket, Jackson won an overwhelming victory over Henry Clay. He claimed he had a mandate to destroy the bank. He ordered his secretary of the Treasury, William Duane, to remove Treasury deposits from that bank and place them in state banks that were affiliated with his new party. When Duane refused, Jackson fired him, appointed his attorney general, Roger Taney, to his place, and had the deposits removed. Jackson's opponents in Congress organized a new political party, the Whigs, to oppose his policies and his exercise of Presidential power. The bank went out of existence in 1836.

By the end of Jackson's term, the national debt had been entirely paid and the government was running a surplus that Jackson's successor, Van Buren, distributed to the states.

Jackson took personal charge of Indian policy. In 1830 he got Congress to pass a law authorizing him to create new Indian lands west of the Mississippi River and to transport Indians there. He then negotiated with Indian tribes, forcing the Chickasaw, the Choctaw, and the Creek to move west. In 1832 he encouraged Georgia to violate an 1831 Supreme Court ruling, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, that was supposed to prevent Georgia from taking over Cherokee lands, and that tribe was removed forcibly after Jackson left office. Many Indians died along the “trail of tears” during these removals.

As the first President whose election rested on a truly popular base, Jackson translated electoral support directly into Presidential power. Jackson also used Presidential power in a nullification controversy. In November 1832, with Vice President Calhoun's support, South Carolina passed a resolution nullifying, or preventing enforcement of, the high tariffs of 1828 and 1832 within the state. In December, Jackson responded with a proclamation to the people of South Carolina warning them against nullification or secession and reminding them of the supremacy of the national government and its law. He warned the citizens who were preparing to defend South Carolina militarily that “disunion by armed force is treason.” Calhoun resigned his office in protest over these tariffs and Jackson's strong stance. In March 1833 Jackson gained from Congress a “Force Bill” giving him the power to use federal force to ensure compliance with the tariff as well as a reduction in the high rates designed to defuse the crisis. After Jackson sent warships to Charleston Harbor, South Carolina backed down, withdrawing its nullification of the tariff on Jackson's birthday.

The struggle between Jackson and Calhoun epitomized the strains that would eventually tear the Union apart. At a dinner in Washington in 1830 Jackson had given a famous toast: “Our federal Union -it must be preserved.” But Vice President Calhoun had responded, “The Union -next to our liberty, most dear.” The question of national supremacy would remain an open issue until the end of the Civil War.

Jackson retired to the Hermitage and lived out his life there. He was still despised as a high-handed and capricious dictator by his enemies and revered as a forceful democratic leader by his followers. Although he was known as a frontiersman, Jackson was personally dignified, courteous, and gentlemanly-with a devotion to the "gentleman's code" that led him to fight several duels.

A forceful, at times violent personality, Jackson continues to provoke controversy among historians, who see in him reflections of both the best and the worst tendencies of the new Republic.

Jackson was a classic example of the self-made man who rose from a log cabin to the White House, and he came to represent the aspirations of the ordinary citizen struggling to achieve wealth and status. He symbolized the "rise of the common man." So total was his identification with this period of American history that the years between 1828 and 1848 are frequently designated the "Age of Jackson."

The greatest popular hero of his time, a man of action, and an expansionist, Jackson was associated with the movement toward increased popular participation in government. He was regarded by many as the symbol of the democratic feelings of the time, and later generations were to speak of Jacksonian democracy.

His period offered new opportunities to the middle class. It was an era of liberal capitalism. Jackson had appeal for the farmer, for the artisan, and for the small-business owner; he was viewed with suspicion and fear by people of established position, who considered him a dangerous upstart.

Jackson's career exemplified, and in many ways molded, the contradictory forces at work in the democratization of the early Republic. In his appeals to the common man, his attacks on privileged wealth, and his help in building a new sort of mass political party, he advanced the causes of equal rights and majoritarian democracy. Yet those advances went hand in hand with the continued subjugation of Native Americans and a determination not to disturb the slavery issue. Jackson stood for a more egalitarian America, but his vision of democracy stopped squarely at the color line.