The Presidents of the USA

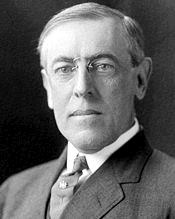

| Born | Dec. 28, 1856, Staunton, Va. |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Education | • Davidson College, 1876 • College of New Jersey (Princeton), B.A., 1879 • University of Virginia Law School, 1880 • Johns Hopkins University, Ph.D., 1886 |

| Military service | none |

| Previous public office | Governor of New Jersey, 1911-12 |

| Died | Feb. 3, 1924, Washington, D.C. |

Wilson was born in Virginia and lived in Georgia and the Carolinas during the Civil War. His father's church was used as a temporary hospital for wounded Confederate soldiers. After attending Davidson College for a year to study for the ministry, he withdrew for health reasons and later went to the College of New Jersey (Princeton), where he distinguished himself as a debater.

After graduating in 1879 he studied law at the University of Virginia and practiced briefly and without much success in Atlanta before deciding to study history and political science at Johns Hopkins University. His doctoral dissertation, which became a highly regarded book, Congressional Government, analyzed the weakness of the Presidency and the strength of the standing committees in Congress.

Wilson embarked on a career as a college professor and eventually in 1902 became president of Princeton. He soon gained a national reputation for his innovative educational reforms at Princeton, which were designed to emphasize academics and de-emphasize its elitism. He transformed a venerable college into a world-class university.

Two years later the Democrats in New Jersey, seeking a candidate with a reputation for honesty and incorruptibility, visited Wilson at Princeton and offered him the party's nomination for governor. After his election in November 1910, he pushed through measures that put the state in the forefront of progressive reform. This success catapulted him into national prominence and led to his nomination on the 46th ballot in the Democratic convention.

With the Republicans split, Wilson was able to win the Presidency with 42 percent of the popular vote, defeating Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. The Democrats retained Democratic control of the House and won a six-seat margin in the Senate.

Wilson, from the beginning, demonstrated energetic leadership and domination of Congress. He influenced the roster of committee members so that supporters of his New Freedom program served on key committees. He imposed party discipline on congressional Democrats to vote for measures put forward by their President. He broke precedent by giving an address to a special session of Congress called in April 1913, instead of sending the legislature a written annual message, as every President since Thomas Jefferson had done. He held regular news conferences and made every effort to rally public opinion around his legislative proposals.

Under his leadership, Congress from 1913 to 1916 enacted the most coherent, constructive, and comprehensive program to that time. It included measures for banking reorganization and control through the Federal Reserve System, tariff reduction, federal oversight of business, support of labor organizations, and federal aid to education and agriculture.

In 1916 Wilson got Congress to approve federal land banks to provide low-interest loans to farmers, workmen's compensation for injuries received on the job, an eight-hour day for railroad workers, and laws prohibiting child labor.

The Seventeenth Amendment, providing for the direct popular election of U.S. Senators, the Eighteenth Amendment, which instituted prohibition, and the Nineteenth Amendment, by which women received the vote, were all launched while Wilson was President.

However, Wilson also promoted racial segregation in government departments in the capital.

In foreign affairs Wilson pursued an interventionist policy against small nations. In 1914 he ordered the military to seize the port of Veracruz, Mexico, to prevent a shipment of German weapons from reaching the revolutionary government of Victoriano Huerta. The crisis ended after European mediators succeeded in getting Huerta to resign. In 1915 the United States occupied the Caribbean islands of Haiti and Santo Domingo and took control of their financial affairs in order to pay back banks that had loaned money to these nations.

In 1916 Wilson sent General John J. Pershing into Mexico with orders to pursue the guerrilla leader Pancho Villa, who had crossed into U.S. territory and killed 19 Americans. But Pershing's expedition was unsuccessful, and after several clashes with Mexican troops it was withdrawn early in 1917.

In 1914, at the beginning of World War I, Wilson issued a Neutrality Proclamation that stated that the United States would not take sides in the conflict. But Germany's policy of unrestricted submarine warfare caused Wilson to protest and eventually to tilt U.S. policy toward Great Britain and France. Although the British also interfered with U.S. shipping, only the German action resulted in the loss of American lives.

On May 17, 1915, the Germans sank a British ocean liner, the Lusitania, resulting in the loss of 1,198 lives, among them 128 Americans. Early in 1916 Germany announced it was ending its submarine warfare, and Wilson then campaigned for reelection on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Wilson won a close election against Republican Charles Evans Hughes, receiving 52 percent of the popular vote.

In December 1916 Germany announced its willingness to negotiate an end to the war. Wilson then called for a peace conference and on January 22, 1917, outlined his ideas for “peace without victory” in Europe. But nine days later, as if in answer, the Germans torpedoed Wilson's initiative by announcing a resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare.

On February 3, 1917, Wilson broke diplomatic relations with Germany. Wilson armed U.S. merchant ships on March 5. On March 18 the Germans sank three U.S. merchant vessels, and on April 6 Congress granted Wilson's request for a declaration of war against Germany.

The U.S. expeditionary force under General Pershing broke the long stalemate at the Second Battle of the Marne. Other troops entered Russia on the side of the anticommunist White Russians fighting the Bolsheviks, and they remained until 1920.

Germany acknowledged its defeat and signed an armistice on November 11, 1918. In December 1918 Wilson sailed for the peace negotiations in Paris. His most notable accomplishment at Paris was to secure the incorporation of the Covenant of the League of Nations into the treaty with Germany. The Allies signed the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919.

But many Americans were not prepared to undertake such international obligations as the Covenant required. A healthy Wilson would undoubtedly have found common ground with the moderate Republicans in the Senate who had reservations about the League and would have achieved ratification of the treaty.

The president, however, after making a national speaking tour on behalf of the League, suffered a severe stroke on October 2, which paralyzed his left side.

For two months Wilson was totally incapacitated. For the remainder of his term, though he understood fully what was happening around him, he was unable to do more than listen, dictate letters, talk for a few minutes, and scrawl his signature. For four months his cabinet did not meet; for another four it met without him. Cabinet secretaries were unable to discuss government business with him.

His wife and the White House physician controlled all access to him. When Secretary of State Robert Lansing inquired if the President was so disabled he should resign, they vigorously denied it. No one in government wanted Vice President Thomas Marshall, whom they considered incompetent, to take over.

Paralyzed and totally dependent on his wife, Wilson was in no position to control the outcome of the struggle for the Treaty of Versailles. The Senate approved it with a series of “reservations” sponsored by Senator Lodge. Wilson called on his supporters to vote against that version of the treaty. In November, a coalition of Republicans who opposed any version of the treaty and Democrats defeated Lodge's version. (In 1921, by a simple resolution, Congress declared the war with Germany over.)

Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1920.

His two terms were characterized by successes in instituting a progressive domestic program. His foreign policies were marked by victory in World War I and military interventions in several nations.

Wilson appealed to a gospel of service and infused a profound sense of moralism into his idealistic internationalism, now referred to as "Wilsonian". Wilsonianism calls for the United States to enter the world arena to fight for democracy, and has been a contentious position in American foreign policy.

Wilson transformed the presidency into the institution we know today by his strong leadership in foreign affairs, his command of public opinion, and his leadership of his party in Congress.