The Presidents of the USA

| Born: | Apr. 23, 1791, Cove Gap, Pa. |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Education | • Dickinson College, B.A., 1809 |

| Military service | State militia, PA (private) |

| Previous public office | ♦ Pennsylvania House of Representatives, 1814-16 ♦ House of Representatives, 1821-31 ♦ minister to Russia, 1832-33 ♦ U.S. Senate, 1834-45 ♦ U.S. secretary of state, 1845-49 ♦ minister to Great Britain, 1853-56 |

| Died | June 1, 1868, near Lancaster, Pa. |

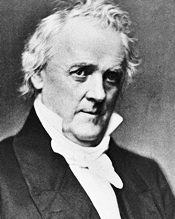

James Buchanan was born on April 23, 1791, on a farm in Lancaster, Pa., the son of a Scotch-Irish immigrant. After graduating from Dickinson College in 1809, Buchanan became a lawyer. As a Federalist, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1814 and to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1820. He was an early supporter of Andrew Jackson's presidential aspirations and became a leading member of the new Democratic party in Pennsylvania. Buchanan was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1834, serving there until 1845. As a senator, he supported Southern demands that all abolitionist petitions to the Senate be immediately tabled without consideration.

At the 1844 Democratic convention, Buchanan was one of the leading contenders for the presidential nomination but lost out to James K. Polk. When Polk won the presidency and formed his Cabinet, Buchanan was named secretary of state. In this position he played a key role in Polk's expansionist policies. He successfully negotiated a treaty with England over the Oregon Territory, thus avoiding a possible war.

At the 1848 and 1852 Democratic conventions, Buchanan was a leading contender for the presidential nomination but was again passed over. In 1853, he was appointed ambassador to England by President Franklin Pierce. While on this mission, in order to win Southern support for his nomination in 1856 he helped draft the Ostend Manifesto, which called for United States acquisition of Cuba, by force of arms if necessary. Returning to the United States in 1856, he received the Democratic nomination for president.

Buchanan was nominated for President as a noncontroversial choice: he had been out of the country during the bruising battles over the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Though his predecessor had been a weak and ineffectual President, the prosperity of the nation made it seem likely to party leaders that they could retain the White House with a candidate who appealed to both sections. Buchanan defeated Republican candidate John C. Fremont and American party (also known as the Know-Nothing party) candidate Millard Fillmore, though he did not receive a majority of the popular vote. Buchanan's base of support was the slave states: he won all except Maryland, which voted for Fillmore.

Buchanan became a “doughface” President -a term for a Northerner with Southern leanings. Buchanan's cabinet, like Pierce's, was balanced between North and South but seemed to have a Southern tilt. Bolstered by the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) that African Americans -whether slave or free- were not citizens and had no legal rights that could be protected by federal courts, Buchanan enforced the Fugitive Slave Act and incensed the Northern wing of his party.

Buchanan had to deal with the Panic of 1857, a financial crisis caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. The financial downturn did not last long; however, a proper recovery was not seen until the American Civil War.

In his first year as President, Buchanan dealt with a challenge to federal authority in Utah. The governor, Mormon spiritual leader Brigham Young, refused to obey federal laws and defied federal officials in the state. Buchanan sent in troops, removed Young, and appointed a new governor. Buchanan reported to Congress that “the authority of the Constitution and the laws has been fully restored and peace prevails throughout the territory.”

Buchanan's greatest failure involved the sectional split over slavery.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 (during the previous administration) had created Kansas Territory, and allowed the settlers there to choose whether to allow slavery. This resulted in violence between "Free-Soil" (anti-slavery) and pro-slavery settlers.

His party split over his support for a Southern attempt to bring Kansas into the Union as a slave state, with abolitionists such as Stephen Douglas opposing him. In a referendum, Kansas voters overwhelmingly adopted an antislavery constitution and compelled Buchanan and Congress to admit Kansas into the Union as a free state early in 1861. Minnesota and Oregon also came into the Union as free states. Northern sentiment swung sharply against Buchanan, and many anti-Buchanan Democrats won in the midterm elections of 1858, among them Stephen Douglas in the Senate contest in Illinois. Buchanan was now fatally weakened, with no following in Congress.

Buchanan's efforts to maintain peace between the North and the South alienated both sides, and the Southern states declared their secession in the prologue to the American Civil War. Buchanan's view of record was that secession was illegal, but that going to war to stop it was also illegal. Buchanan, first and foremost an attorney, was noted for his mantra, "I acknowledge no master but the law."

After the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union. Buchanan denounced the secession but did nothing to enforce the laws of the United States, hoping for a peaceful solution. In his message to Congress in December, Buchanan observed that a state had no constitutional right to secede from the Union, but he argued that no state could be compelled to remain. He warned the Northern states that if they did not repeal their laws obstructing the execution of the Fugitive Slave Act, “it is impossible for any human power to save the Union.” He defended his inaction against secession by arguing, “The Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war.”

Although seven states in the lower South seceded and formed the Confederacy on February 20, 1861, eight other border and Southern slave states remained in the Union, awaiting the results of efforts to compromise. Buchanan's goal was to keep these states from seceding. When he sent a ship, Star of the West, to reinforce Fort Sumter, South Carolina, with 200 troops, shore batteries fired on the vessel and forced it to withdraw. Yet Buchanan did nothing to provoke the remainder of the slave states, lest they leave the Union. To advance Buchanan's notion of a compromise, a peace convention was held in Richmond, Virginia, under the chairmanship of former President John Tyler, but even before his inauguration Abraham Lincoln rebuffed the compromise proposals introduced there.

The Civil War erupted within two months of Buchanan's retirement. He supported it.

However, Buchanan spent most of his remaining years defending himself from public blame for the Civil War, which was even referred to by some as "Buchanan's War".

Buchanan caught a cold in May 1868, which quickly worsened due to his advanced age. He died on June 1, 1868, from respiratory failure at the age of 77 at his home at Wheatland

James Buchanan was a loyal Democrat; as President he did all he could to hold his party together by adopting a conciliatory position on slavery. As a Northerner, he opposed slavery in principle, but he was willing to protect the rights of slaveholders under the Constitution. His inability to see that his first responsibility was to the Union rather than to sectional compromise cost him his office and created the conditions for the Civil War.

The last of a series of presidents who dealt ineptly with rising sectional tensions, Buchanan had neither the vision nor the talent to defuse the crisis. Although he was devoted to the Union, his one-sided pro-Southern policies were disastrous for the Democratic party and the nation. Few presidents have entered office with more experience in public life, and few have so decisively failed.

When he left office, popular opinion had turned against him, and the Democratic Party had split in two. Buchanan had once aspired to a presidency that would rank in history with that of George Washington. However, his inability to impose peace on sharply divided partisans on the brink of the Civil War has led to his consistent ranking by historians as one of the worst Presidents. Historians in both 2006 and 2009 voted his failure to deal with secession the worst presidential mistake ever made.