The Presidents of the USA

| Born: | Nov. 2, 1795, Mecklenburg County, N.C. |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Education | • University of North Carolina, B.A., 1818 |

| Military service | Tennessee militia, 1821 (Colonel) |

| Previous public office | ♦ Tennessee House of Representatives, 1823-25 ♦ House of Representatives,1825-39 ♦ Speaker of the House, 1835-39 ♦ governor of Tennessee, 1839-40 |

| Died | June 15, 1849, Nashville, Tenn. |

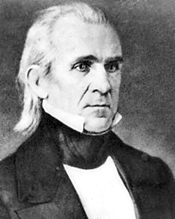

James K. Polk was born on Nov. 2, 1795, in Mecklenburg County, N.C. As a child, he moved to an area in Tennessee settled by his grandfather, a land speculator. His mother, a devout Presbyterian, made an indelible impression on his character, instilling Calvinistic virtues of hard work, self-discipline, individualism, and a belief in the imperfection of human nature.

After graduation from the University of North Carolina in 1818, he studied law under Congressman Felix Grundy and was admitted to the bar in 1820. Elected to the legislature in 1822, Polk became known as an opponent of the state's banks and land speculators. He supported Andrew Jackson, who was an old friend of his father, for the presidency in the election of 1824.

Polk courted Sarah Childress, and they married on January 1, 1824. Polk was then 28, and Sarah was 20 years old. They had no children. During Polk's political career, Sarah assisted her husband with his speeches, gave him advice on policy matters and played an active role in his campaigns

As a Jacksonian, Polk was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1825, becoming a leader of his party. He advocated a strict states'-rights position, emphasizing the desirability of an economical government. As chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee from 1833 to 1835, he supported Jackson's banking policies, including removal of the government's deposits from the Bank of the United States. As a reward for his support, Polk was elected Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1835 and served until 1839. He vastly increased the powers of the Speaker's office by assuming the burden of guiding administrative measures through Congress. He was governor of Tennessee from 1839 until 1841; he was defeated for reelection in 1841 and again in 1843.

Polk made a political comeback in Presidential politics in 1844. He favored the annexation of the independent nation of Texas and negotiations with Great Britain to acquire territory in the Northwest, which later became known as the Oregon Territory.

He received Jackson's support over John Tyler, who opposed annexing Texas. Polk was the Democratic party's first dark horse, or unknown nominee, winning in a sectional compromise on the ninth ballot. He was the compromise candidate among several contenders.

The word was sent from Baltimore to the capital by telegraph—the first use by a political party of Samuel F. B. Morse's new invention—and the recipients thought the machine was not working because it seemed so improbable that Polk was the nominee.

In the Presidential election Polk's rival, Whig candidate Henry Clay, exclaimed, “Who is James K. Polk?” The Democrats took up the question as a defiant campaign slogan, and in a fierce campaign Polk defeated Clay, receiving 49.6 percent of the popular vote to Clay's 48.1. At age 49 he was the youngest person yet to serve as President.

To attract John C. Calhoun's partisans, Polk adopted an expressionistic platform, emphasizing the incorporation of all the Oregon Territory and the annexation of Texas. Clay's last-minute endorsement of Texas annexation cost him the election, as it forced 15, 000 antislavery Whigs to defect to the Liberty part.

On May 9, 1846, Polk laid before his cabinet a proposal for a declaration of war, on the grounds that Mexico had refused to receive his envoy and had refused to pay damage claims for losses of U.S. lives and property. Just that evening, word reached the capital that there had been a skirmish between Mexican and U.S. forces that had resulted in death or injury to 16 U.S. soldiers. Polk had Congress declare war on May 13, 1846, saying that Mexican forces had “invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.” In fact, the events occurred in disputed territory after U.S. forces trained their cannons on the town square of Matamoros.

The war was a military success: General Winfield Scott captured Mexico City on September 14, 1847, while Colonel Stephen Kearny took control of New Mexico and California. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed February 2, 1848, ended the war. The United States took possession of the Mexican provinces of Upper California and New Mexico, and the two countries established a border at the Rio Grande in Texas. Polk agreed to pay Mexico $15 million for the territories and also to pay $3,250,000 in claims made by U.S. citizens against Mexico.

Nevertheless, the treaty was unpopular with abolitionists in the North, who saw it as a way to extend slavery. Ulysses S. Grant, who served in the war, called it “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.” Abraham Lincoln, a Whig member of Congress at the time, devoted his first speech in the House of Representatives to criticizing Polk's decision, saying that Mexico “was in no way molesting or menacing the United States.”

Needless to say, the Mexicans have never forgotten Polk for taking away half their nation. In 1848 Polk's effort to buy Cuba for $100 million was rejected by Spain.

In domestic policy, Polk secured passage of the Walker Tariff Act of 1846, which reduced tariffs, or taxes on imported products, and thus fulfilled a campaign promise popular in the South and among farmers. He later blocked the Whig programs of high tariffs, federally funded internal improvements, and a national bank, which the Whigs proposed when they took control of Congress in the midterm elections of 1846. Polk also vetoed measures to use federal funds to improve rivers and harbors.

the Democrats lost control of the House in 1846, and his aggressive war policy provoked the Wilmot Proviso aimed at excluding slavery from the territories taken from Mexico. Although the proviso was not passed by the Senate, the principle that Congress could exclude slavery from the territories became the focus of the Republican party.

By 1848 Polk, myopic about the immorality of slavery and the modernization of the nation, was cursing "southern agitators and northern fanatics." His policies led eventually to disintegration of both major parties and the sectional crisis of 1849-1850.

Polk was exhausted from his efforts to hold his party together and fend off the Whig majority in Congress, and decided not to seek a second term. His last message to Congress spoke of an “abundance of gold” in California, setting off the gold rush of 1849.

Polk died during a cholera epidemic shortly after leaving office.

Polk had the shortest retirement of all Presidents at 103 days. He was the youngest former president to die in retirement at the age of 53.

Humorously, Sam Houston is said to have observed that Polk was "a victim of the use of water as a beverage.

Scholars have ranked him favorably on the list of greatest presidents for his ability to set an agenda and achieve all of it. Polk has been called the "least known consequential president" of the United States.

He is recognized, not only as the strongest president between Jackson and Lincoln, but the president who made the United States a coast-to-coast nation. When historians began ranking the presidents in 1948, Polk ranked 10th in Arthur M. Schlesinger’s poll. and has subsequently ranked 8th in Schlesinger’s 1962 poll, 11th in the Riders-McIver Poll (1996), 11th in the most recent Siena Poll, 9th in the most recent Wall Street Journal Poll (2005), and 12th in the latest C-Span Poll (2009).

While Polk’s legacy thus takes many forms, the most outstanding is the map of the continental United States, whose landmass he increased by a third. Polk was the first President of a coast-to-coast USA.